Amanda Davies is a Tasmanian artist I have admired for a long time, so I relished the opportunity to sit down with her in her own personal workspace, for a conversation about her art.

She was a delight to talk to: warm and engaging, considered and generous – but ever-so-slightly formidable. A standout among Australian figurative painters. And so it is with some trepidation that I attempt to write about my impressions of her, the artist, and her work.

Amanda’s studio turned out to be in a converted chicken shed, on the side of a hill, on the Tasman Peninsula at Premaydena.

The Peninsula is a place of beauty and dark histories, including the history of Port Arthur. Premaydena itself is close to another former penal settlement, Saltwater River, now a small town of sorts with a population of about 130 – known by the convicts back in the 1800s for its particularly harsh conditions. The Salt Water River post office opened in December 1878 but by 1970 it had closed. By the 1970s the peninsula as a whole was struggling economically, as apple production and dairy farming declined. Mainlanders in search of cheap land, and seeking an alternative lifestyle started moving into the area, mingling with the rather surprised locals. Some farmers were selling off parcels of land to the newcomers, while others were building large chicken sheds for the commercial production of poultry; seen as a new and more commercially viable form of farming.

Amanda and her partner (fellow artist Colin Langridge) live in one of these sheds which they have architecturally transformed into a smart modern home; whilst they each have their own converted chicken shed as a studio, close by on the same property, nestled into their rambling garden. Amanda’s is a vast elongated space set up as a creative cloister.

Amanda is a figurative artist, often using herself as the model – the subject of the painting – placing herself at the centre of an experiment. Sometimes nude – or not. Sometimes using props, sometimes placing herself in awkward or distressing situations, she takes hundreds of photos of herself in deliberate, staged poses, before she starts to paint.

The studio is large and the couch is centre and back, dominating its isolated position; the single piece of furniture on her set, for one of her staged/photoshoots prior to painting.

She generously shows us the props for a piece she is starting to conceptualise. It will involve her own body, will reference art works by the Tasmanian painter, Owen Gower Lade (1922 – 2007), and will be set up on the couch. She talks about the process, about Owen Lade himself, and shows us the works she painted on fabric, based on some of Lade’s portrait paintings, mostly of children. She had produced these works on fabric then cut them out, intending them to drape and fold over her own body, one photo at a time, to form a family of individuals (probably, she thought) on the couch. “So it’s about a group, I suppose. A group portrait. But I don’t know what they’re going to look like yet. I know it’s going to be in here. And this is the limitation of the set”.

As she talks to us about working on this new piece, she holds up the bundle of mostly life-sized portraits she had painted on fabric – like a two dimensional floppy family. But she seems resistant to sit on the couch with them as I’m taking photos, leaving that part for the final setup. The couch is kept clear, remaining part of the stage, where the action for the painting takes place. A couch whose only purpose is to be part of the scene.

“When I do sit on that couch, it’s part of a stage”

Sometimes Amanda photographs herself from above (either full body, or just her face) while she lies on the floor – which gives the figure in the finished work, hanging vertically on the wall, a slightly disconcerting perspective. She did this with a series of paintings where she smeared toothpaste on her face. One of these self-portraits was selected as a finalist in the 2018 Archibald Prize.

Apparently she had come across a story of a woman who inadvertently smeared some toothpaste on her face, instead of moisturiser. Toothpaste is astringent, it reddens the skin, and stings. The end result was a series of paintings with Amanda in a sliver of time and emotion. Vulnerable. A transcendency of sorts.

“I don’t start off with it as a series….I just keep making work”.

“I try not to have a formula. That I’m going to producing ‘this'” she explains.

“It has to have a bit of a life of its own.” In a sense, the aim of putting brush to canvas is to create an independent organism; to create an entity that can stand up for itself, on its own terms. The emphasis is on the execution of the markings, the blinkering of external perceptions, banishing anxiety, and the attempt to allow the painting itself to be the critic.

The canvas is a court where the artist is prosecutor, defendant, jury, and judge. Art without a trial disappears at a glance: it is too primitive or hopeful, or mere notions, or simply startling, or just another means to make life bearable. You cannot settle out of court.

In correspondence subsequent to our meeting, Amanda quotes the artist Philip Guston from his essay Faith Hope and Impossibility (originally published in Art News Annual XXXI, 1966. Adapted from notes for a lecture at the New York Studio School in May 1965).

“You feel as you go on working that unless a painting proves its right to exist by being critical and self-judging, it has no reason to exist at all—or is not even possible. The canvas is a court where the artist is prosecutor, defendant, jury, and judge. Art without a trial disappears at a glance: it is too primitive or hopeful, or mere notions, or simply startling, or just another means to make life bearable. You cannot settle out of court.”

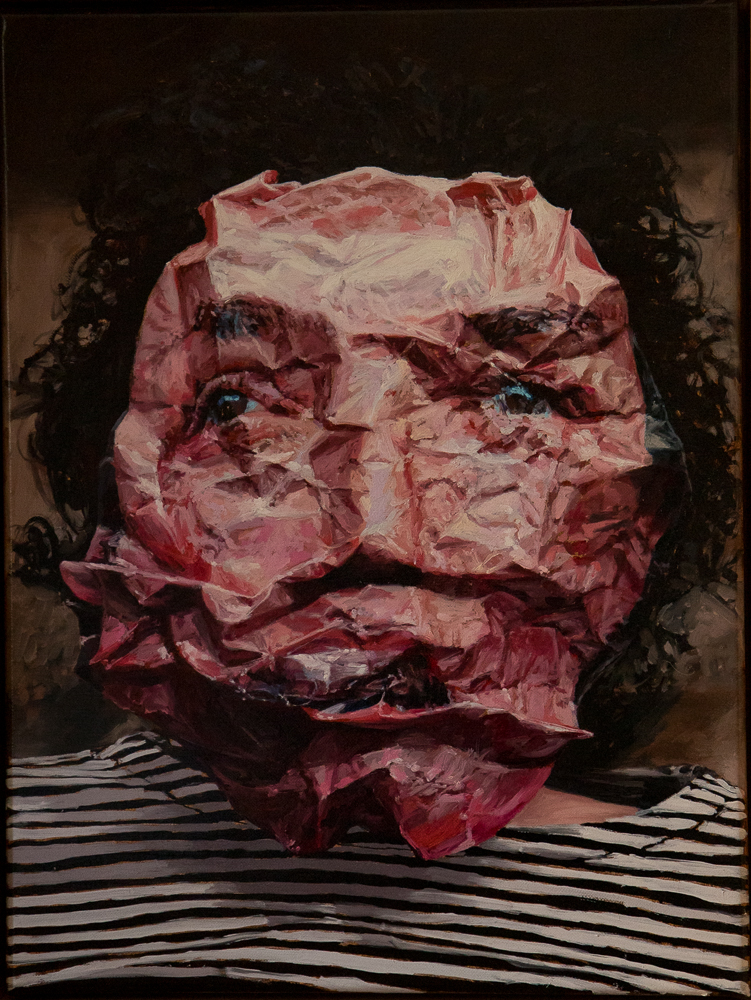

Amanda’s 2021 painting, Tasmanian Mother (again) Portrait of Lisa Campbell-Smith, is a portrait of Lisa Campbell-Smith, a curator and arts producer currently working at Contemporary Art Tasmania. Amanda first painted the portrait on paper, then scrunched it up. Finally, the scrunched up paper was placed over Lisa’s face, in the execution of the final portrait. The result is a portrait (oil on linen) that shows the fine lines of the creases on the scrunched paper – a thin veneer of a mask over the subject’s face. Lisa’s black hair (loose behind the mask) and her striped top are all that’s left of what might be immediately recognisable as her.

Tasmanian mother (again) Lisa Campbell-Smith, 2021. Oil on canvas. 40 x 30cm. Private collection Hobart.

Amanda’s work can be enigmatic – sometimes even unsettling or disturbing; but when asked about this, she thinks for a moment, acknowledging that “there might be dark in there”, but insists that it was not purposeful, that she isn’t “purposely coming in, saying that’s the flavour I want”. Rather, she tells us, it could just be something in the colours she is choosing. And that at times she could just be painting humorously. As with the portraits of herself with balloons as appendages.

The impression I have is that when Amanda paints, there is a starting point, an idea. She sets it all up – the essential work of research, props, and photographs – before she embarks on the piece itself. And then, it becomes all about the paint and where it takes her.

Paint is evident everywhere in our conversation with Amanda.

She says, ”I’m not thinking about what it means. I’m just thinking about painting and creating the paint. I don’t think about it because if I think about it, it will all unravel.”

“I like sculpting, in paint, so that a flat object – I have to give it form. I have to animate it. It’s the same with the figures I suppose, I have to animate them, I have to bring them back to form”.

Amanda is working in a time when movies and streaming series sometimes rely on plots where a main protagonists turns out to be an alien, or an android. That plot enables a moral complexity that might not otherwise be present. But it can be very contrived and often produce only banality. Amanda doesn’t use aliens androids or robots for complexity, instead she often just uses her own body, a stage, various props – and paint.

There is a layer of the subconscious in her work. The self, with all its weaknesses. The fissures in the walls of the self, and the leaks and seepage along the way, that we normally work hard to keep contained. Or the masks that we use to hide ourselves from others. We pull back from exposure, but it’s the fissures and cracks which expose the vulnerabilities that can lead to a connectivity with the world, and with others – other selfs. Unfurling the humanity in our selfs can also reveal the resultant damage from just being human, and on occasions the humour of being human. The fleshy human self, along with all its fleshly bodily functions is so terribly humorous at times – which all means that Amanda is laughing with us not at us. She teases out what it means to be human – toothpaste, balloon appendages, bandaids and all.

View some of Amanda’s work in The Stock Room at Bett Gallery, here.

A lot of her work demands an emotional response, at least from me they do.

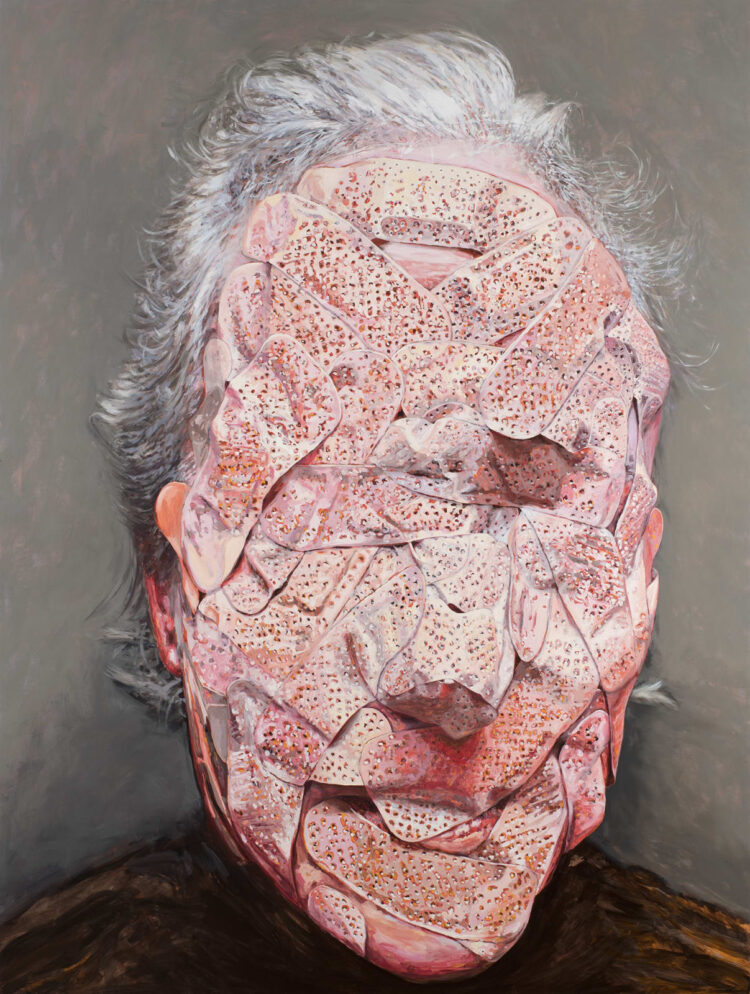

Bandaids can be seen in a quite a few of her paintings. In part, they come from her interest in the stigmata which dates back to her residency in Rome, in 2013. She has painted potatoes, faces, pinboards, and landscapes with bandaids on them. Her large landscape work, X marks the spot_Arrangement in flesh tones_View from the artist’s studio in Premaydena, which was shortlisted for the 2022 John Glover Prize for Tasmanian Landscape Painting, is pale pink – flesh-tones – with a bandaid painted in the corner of one of the paddocks.

The bandaids add a poignancy. They mark the damage, contain the wound, and control the seepage. They show us our humanity. They hide a potentially unhappy human reality behind an everyday disposable Discount Chemist product.

Talking about the stigmata Amanda says, “I like the stigmata and Francis of Assisi. I’m really interested where the wound is, the body is not well contained. I do like that thing, about things being unconfined. This seepage is an opportunity for something new…to become.”

One painting of Amanda’s, which I keep coming back to, again and again, is her portrait of Pat Brassington (for which she was awarded the Portia Geach Memorial Award in 2017). I understand that they have a close friendship. And to me, the portrait itself is evidence of that. It is a very personal painting, showing her fellow artist with all the contradictory elements of an openly loved human being; looking like a vulnerable, wise, nonconformist, dressed in a secondhand wedding gown bought from an op-shop, dyed black, and worn inside out. Not all the layers of the dress took the dye well. Nylon doesn’t. The bra cups, inside out, look like mini satellite dishes, and the lips are smeared – Pat Brassington’s surreal essence is seeping out.

Amanda emphasises the need for an element of chance in her paintings. “There has to be a gap in the image, in the modelling. There has to be some energy there.”

And to the bottom right of her portrait of Pat Brassington there is an electrical powerpoint. A domestic detail, grounding the playful, slightly disturbing image. It does not draw your eye, but just sits there in all its ordinariness, in the corner of the painting.

PORTRAIT OF PAT BRASSINGTON. Oil on linen. 107 x 122 cm. Private collection, Hobart

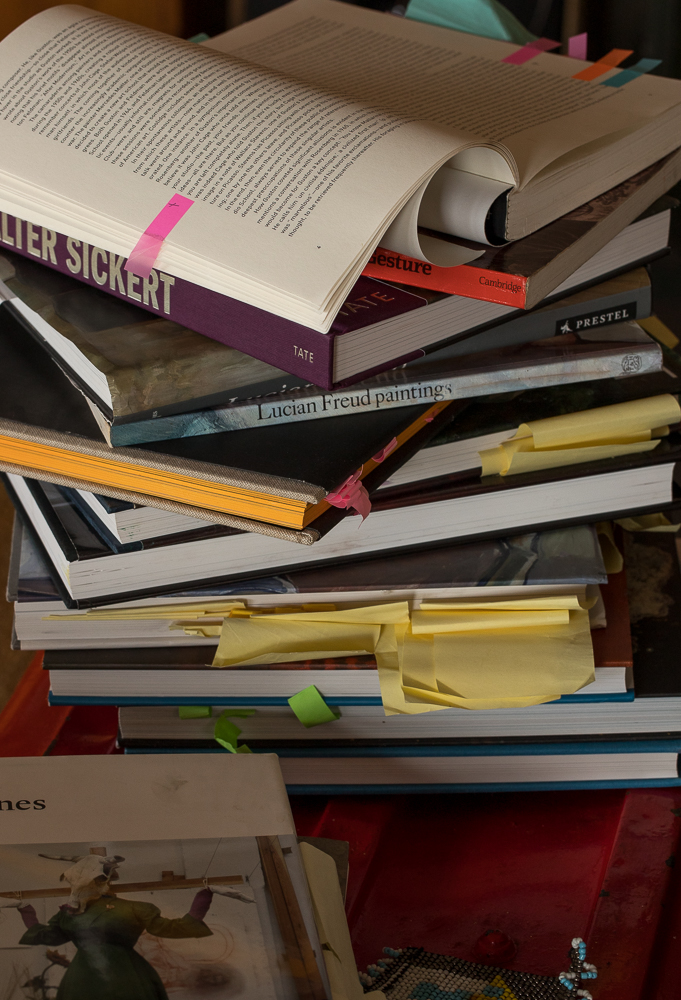

When Amanda invites us into her house, the first thing I notice is the art books – stacks of large reference books, heavily tagged with colourful Post-it notes. These are books about individual artists, which include large, coloured plates of their work that Amanda has pored over. She explains how she spends time studying how other very good painters, paint. She animatedly opens a book on Diego Velazquez, to a plate which shows off his painterly techniques. She points out the thin application of paint here, and the beautiful translucent colours there. The book is heavy with Post-it notes.

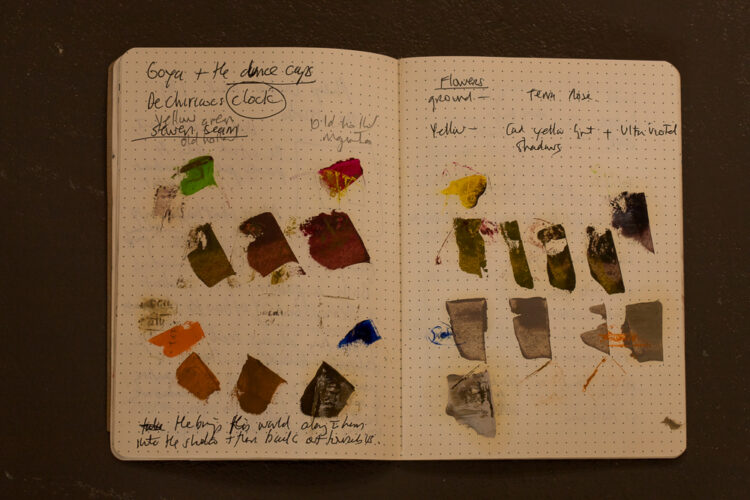

She also shows us her notebook where she has written out, and sometimes reproduced, the palettes of different artists or art periods. “I’ve put the Impressionists’ palette down. This is a classical paint palette. It gives me a base…I don’t lay my palette up like that.”

The book is full of lists of paint colours and reproductions of individual palettes attributed to various artists. She generously offers to grid up her own palette for us in the studio, but I decline because of all that it involves – her time and paint, both precious commodities. A decision I later somewhat selfishly regret, after I realise the significance of what she had offered.

Amanda’s notebook, showing some of Goya’s palette.

As you would expect, her studio has a large workbench covered in her tubes of paint, with large containers of low toxic paint solvent stored underneath, and a wall splattered with residual paint with screws for hanging the canvases that are in progress. She paints standing up.

On a couple of occasions, Amanda talks to us about painting objects in such a way as to animate them, to give them form. But in the end she says, “What I’m interested in though, is the subtleties of colour and tone. So I’m chasing that…And I’m interested in light.”

We discuss painting skin, the colours and tones involved, and how that can be a motivator in itself for starting a particular painting.“Skin itself is layered like painting. And that’s what Jenny Saville talks about. She talks about painting being layered like the skin. You’ve got the tone and the undertone and colours coming through.”

She refers to: “The beautiful colours (of the skin).” But then later she adds, “I mean, I do like decay.”

Found object hanging on the wall in Amanda’s house.

It wasn’t quite accurate for me to say that the first thing I noticed in Amanda’s house was the books. The first thing I really noticed was Amanda. I couldn’t take my eyes off her. I have seen so many of her portraits, where she uses her own face or body as the subject, that when we walked into her house I felt I was standing in front of one of her paintings. She was very hospitable. She fed us a delicious homemade goats cheese and homegrown garlic tart, and gifted us each a jar of her honey. It was as if one of her paintings had taken form, then life.

And, I don’t quite know why, but I was intrigued to see that Amanda grows Dahlias; in a hothouse all of their own. Those rather old fashioned, brightly coloured, sometimes spiky flowers which remind me, for some reason, of floral cartoon characters. A vase of these over-achievers, sat on a small table next the huge stack of art books with their protruding fluorescent Post-it notes. They are the happiest, most colourful of flowers.

Amanda spoke to us animatedly about many other artists, including Paula Rigo. Like Amanda, Paula stages herself in the studio. “I really like that approach, because then you’re the artist, you’re the sitter. You’ve got control, you’re the performer.”

And she spoke of John singer Sargent and the importance of gestures in his paintings.

But in the end, it’s all about the paint.

“It’s so exciting to see what the paint can be and do, and make you feel. And the story. And the strangeness. It’s very strange. And that’s intriguing. He [Velazquez] would say he’s not trying to paint a picture. He would say he’s trying to create something happening and his paint becomes a thing in itself. He talks about being able to leave the studio when the painting doesn’t need him anymore and it’s its own being.”

Amanda Davies’ next exhibition, Premaydena Studio, is on at Bett Gallery from 25 October 2024 to 16 November 2024.

Amanda Davies is represented by Bett Gallery.

Bett Gallery site: pdf of Amanda Davies’ CV here.

Article by Chris Tilley

Photographs by Chris Tilley

Hobart, Tasmania

Chris and I felt that to try to understand Amanda’s work we both needed to write out our thoughts. So, here is my take on her paintings. Delia Nicholls

A couple of years ago, my SouthernSalon collaborator, Chris, told me about Amanda Davies, a painter she found intriguing, so I checked her works online. Some are hard to look at and even harder to talk about, others are so unexpectedly absurd that I laughed. Initially, I studied her head-and-shoulder portraits in oils: a fine featured, white-haired youngish woman. After a while I realised the images were self-portraits.

The paintings aren’t large – about the size of the average desk-top computer screen. I found the endlessly idiosyncratic portraits disquieting. They jangled with my self-perception.

Why is she showing herself this way? Her face grimacing in pain; or a look of longing; another of her face settled into resignation; an image of Amanda, I assume, in a Tasmanian devil mask with a hand gesturing a subtle ‘fuck-you’.

The feelings are familiar, but to see them portrayed in oils on canvas takes them across an imaginary and dangerous border. The un/masked artist caught in the privacy of her true feelings.

In revealing herself Amanda is revealing what we cannot see: we don’t see ourselves reacting to our emotions; we feel our body’s response but we cannot visualise that felt experience. We only see how others react.

There are also images of dark humour: a red-headed woman, head and shoulders, framed into a corner with long, black condom-shaped balloons attached to her upper eyelids. A female figure prone, face down with a slick black balloon taut and oversized emerging from her buttocks. Again, that figure, same position with two pale pink balloons perkily protruding from her buttocks.

Untitled (2015) Oil on canvas, 41 x 61cm. Image courtesy of the artist and Bett Gallery.

Untitled (2015) oil on linen, 25.5 x 35.5cm. Image courtesy of the artist and Bett Gallery.

I talked with a friend working in the commercial art world and he questioned who would want to buy such disturbing work. I hadn’t gone there. But it is a valid question. I read an essay written by curator Eliza Burke in which she quotes Amanda saying she understands the work she does doesn’t appeal to the commercial market and says, “but I can’t think about it like that. I’m just thinking about making the best possible, most engaging, interesting, exciting painting work that I can make.”¹

Artists have no obligation to comfort us, and Amanda’s works certainly threw me off balance into thoughts I prefer to avoid.

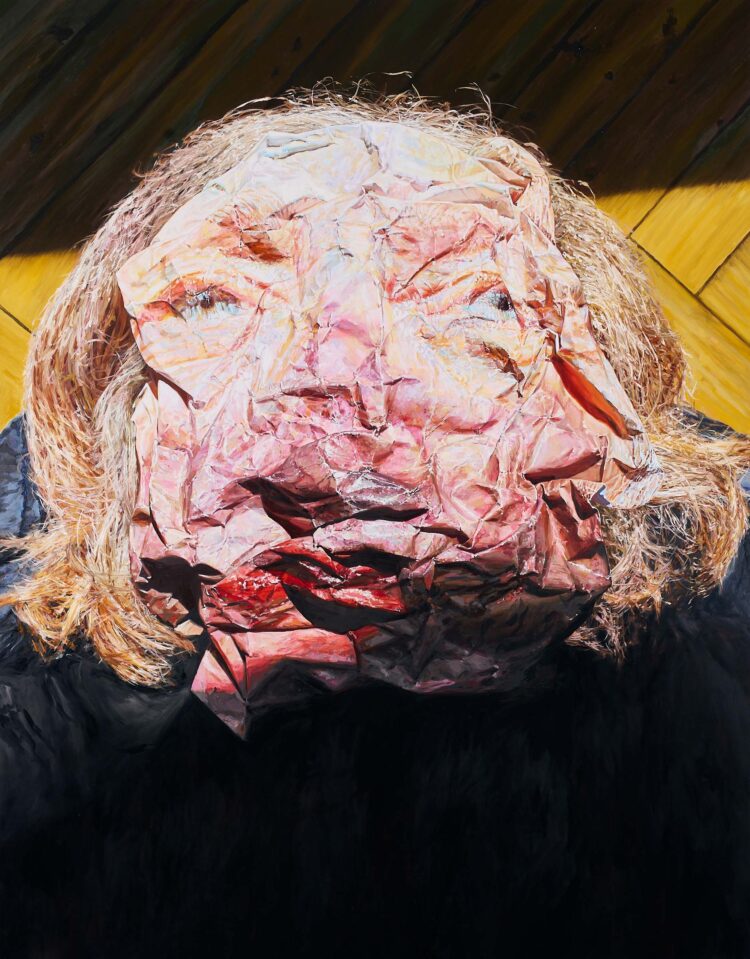

Her images also dismantled my comfortable expectations of portraits: what sort of imagination photographs a patron, prints the image onto brown paper, crushes the bag and then paints that crumpled, eerie result? In our emotionally trigger-ready visual world, irony is a risky path.

Head of Penny Clive (2024), 246cm x 194cm x 3.5cm, Box Tas Oak Frame In 2022 Penny Clive invited Amanda to take up a two-year Detached Inc Artist Residency. Amanda painted a series of portraits of her patron entitled More Beautiful Than They Think.

Image courtesy of the artist and Detached.

In September 2022, Chris and I visited an exhibition of Amanda’s 30 paintings at the Derwent Valley Arts Centre in four rooms of the original 1825 asylum at New Norfolk, an historic town north-east of Hobart. The exhibition was called Vent, and the paintings expressed a world view beyond the personal. They told a story of what institutions do to people, and what this particular facility masked behind its refined Georgian facades. The people portrayed in the works were faceless, absent beings. It was thoughtful and evocative but not exploitative.

Amanda has a deep, professional understanding of institutional care. When she’s not painting, she is an occupational therapist guiding a team who work with older Tasmanians, so they can live well in their homes or access aged care

The more I researched, the more compelling Amanda’s works became and I no longer flinched – although it did fluster me – when I came upon an unusually large, two-metre square portrait of her band-aid encrusted face in the stock room of Hobart’s Bett Gallery.

Treatment in Pink (2019) oil on linen, 244 x 183cm. Image courtesy of the artist and Bett Gallery

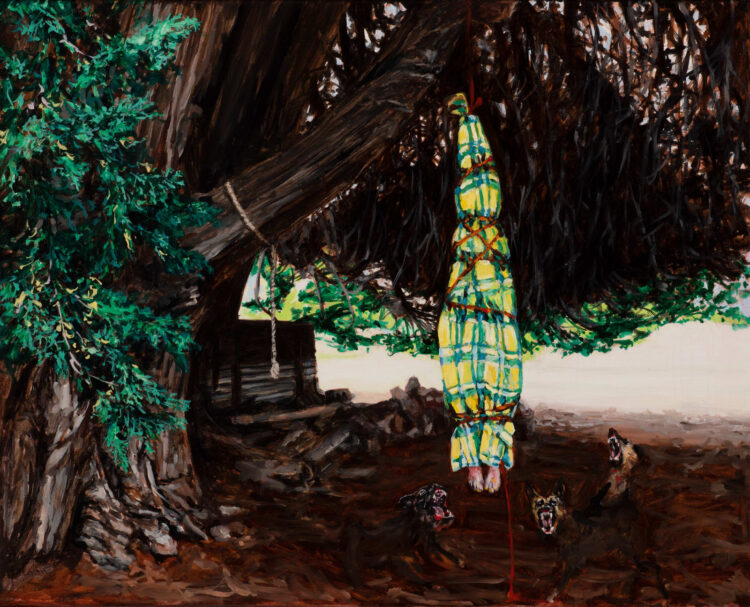

I also found images of a different series of paintings Amanda was asked to create, in 2020, by actor Marta Dusseldorf’s Archipelago Productions for the Angus Cerini play, The Bleeding Tree. One included a slender shape fully wrapped and red rope-bound into a yellow and green plaid blanket suspended from a tree. Baying hounds surround the figure, fangs only centimetres away. It was viscerally frightening and yet the perky colours of the blanket draw the eye and lighten the scene. (I wondered if Amanda posed for this work. She told me later she had created the scene using a pulley system to position her body in a tree and then had it photographed.) The play has that same tension: a dark story of female survival and revenge laced with moments of wicked absurdity.

The Blanket (2020) oil on linen, 41 x 51 cm. Image courtesy of the artist and Bett Gallery.

Chris and I decided we wanted to interview Amanda for SouthernSalon. Just prior to that meeting I was visiting a friend’s home to celebrate Kathy Morano, who had managed the Australia Council’s Greene Street Studio in New York from 1976 to 2016. Across the dining room I saw a pale, slender face framed by white hair that looked distinctly familiar; it was animated and expressive not stilled by paint. And she was laughing – something I had yet to encounter in her work, but I was sure it was her – Amanda. Of course, I introduced myself.

Chris and I drove the 90 minutes to the Tasman Peninsula where she lives with partner, artist Colin Langridge. The property was once, in the late 20th century, a chicken farm for breeding plump little birds for eating. A.J. as Amanda is called by friends, and Colin have converted one of a number of long galvanised sheds into a simple, elegant home; another is her studio, and another Colin’s. They grow vegetables, flowers and keep honeybees.

Amanda’s chook shed studio. One of a number on the Premaydena property.

Image: Amanda Davies

Amanda talked of the artists who intrigued her and of her interest in the light, psychology and drama of Diego Velázquez and Francisco de Goya. The colours of Giorgio Morandi, Camille Pissaro and James McNeill Whistler along with the gestures of the people painted by John Singer Sargent. She admires the skin tones created by Jenny Saville and Lucien Freud; how Philip Guston said he was not trying to paint a picture, rather he was trying to create something that embodies paint and it becomes a thing in itself.

I also learned the internet offers us access to various interpretations of famous artist palettes and the colours used.

One artist she didn’t mention on the day was the Belgian painter, Michaël Borremans, who another friend suggested Chris and I explore in our journey. When I asked Amanda, by email, if she knew of him, she said she did and mentioned his staged figure paintings and his exquisite but sometimes violent scenes. Borremans also sets his scenes and photographs them for later painting.

Amanda says she seeks to portray humanity rather than a human being. Borremans has expressed a similar approach. Like him, I realise she is often using playfulness and disquiet to keep the viewer uncomfortable and curious.

Borremans studies the Old Masters, their style and colour. And that’s where Amanda’s interests also lie, “I suppose like all painters who are interested in the history of painting, we oscillate between the past and the present, trying to locate ourselves and our practice as it develops, trying to create a sensory response, an ‘atmosphere’ and a connection, aiming for the painting not to be about illustrating a subject but about the mark of colour and light and then some, keeping it real, balancing the open coloured space and the realism and feeling of the moment,” she says.

But unlike Borremans, who does not place himself in his works, Amanda is often the punchline in her images.

When I ask her about this, she says using herself is powerful. “This is a private space. I can do what I want. I’ve got myself and the camera. I try to keep it simple – not theatrical. I have to be open about my own body. I’m 56 this year, and I find it really challenging to be naked. It’s risky, but it’s also our power as women to claim being the sitter, the artist, the muse.”

Reclining female nude (2024) oil on linen, 40 x 30cm.

Courtesy of the artist and Bett Gallery. This work is from Amanda’s 2024 exhibition at Bett Gallery.

Throughout history, women painters have used themselves as subject and object. They did so to overcome censorship, chauvinism, shame, and society demands, but Amanda’s self-portraits are not about her physical frame. Her ideas form, she says, as a question arises and she begins to explore it. She creates her scene, photographs herself and then sets out on her journey with paint and light. “It’s so exciting to see what the paint can be and what it can do, and the story or the strangeness. The strangeness is very intriguing,” she laughs, ”It’s very strange.”

To me, the works celebrate an instinct that has often been used against women: our openness to our feelings. Amanda says her works are not about feminism, nor is she interested in the macabre but she is compelled to celebrate and reveal the humanity of our worldly unease and it is that which connects us all.

¹ Interview, Face Off, with curator Eliza Bourke, 2018.