In 2016, I wrote a piece for Island a Tasmanian literary magazine, about a bulky, battered hand bound scrapbook of black ink drawings, and memorabilia. The scrapbook had been obsessively compiled for more than 70 years by a Sarah Elizabeth Emma Mitchell who lived from 1853 to 1946. After her death, Sarah’s niece Grace Mitchell donated the scrapbook and some of her diaries and family records to the Royal Society of Tasmania, along with other diaries to the East Coast Heritage Museum in Swansea.

When you first see its browning, tattered pages, bursting seams and clumsy stitching you might wonder why the Society accepted such a shabby package. However, its seemingly unskillful exterior belies its until now unknown panoramic story.

The scrapbook is Sarah’s memento mori honouring her older, and possibly bolder sister who died tragically of hydatids within a year of marrying the Reverend John Aubrey Ball of Bright, Victoria.

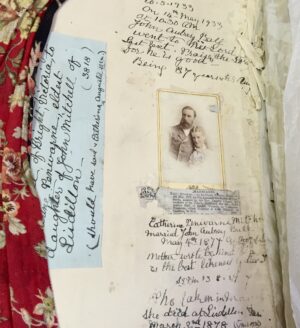

Sarah Mitchell scrapbook: inside front cover showing image of Catherine Penwarne Mitchell and John Aubrey Ball, engagement announcement in 1877.

Catherine Penwarne Mitchell, Sarah’s beloved sister, was born in 1847 and died in 1878. Without this scrapbook we would know nothing about her and how she and her family lived in a remote village in Tasmania.

Their father, John Mitchell (1812 to 1880) was a propertied and politically successful member of the Tasmanian Legislative Assembly.

Kate was no demure colonial lady, she was an ambitious, original artist intent on drawing images of her life and her community. She was also “excessively strong willed and rather sturdy and obstinate” according to a visiting British phrenologist, Mr G Sloper. Endorsement of his services to the colony were advertised in the Tasmanian, December 22, 1868. Kate was only 22 years of age at the time. While we would find his methods to be pseudo-science, it seems his evaluation had some merit.

Fine copperplate notes on Kate’s personality as evaluated by Mr G Sloper a visiting British phrenologist.

In early 2022, the artist Jane Giblin contacted me. She had read my essay and asked if we could meet. Jane told me she had been shown Kate’s drawings by a relative, and was fascinated to see Kate had drawn images of one of Jane’s 19th century ancestors, Minnie (Emily) Giblin.

Jane was inspired to study Kate’s drawings and to learn more about this unique young woman. Like Kate, Jane loves drawing in pen and ink, and she has studied and taught printmaking. She saw potential for a doctorate degree: she would research, write and prepare artworks that responded to Kate’s drawings.

As she researched, she found no other male or female artists in the Australian colony had recorded everyday life in pen and ink drawings – apart from the occasional private journal.

Kate was an unconventional artist but not the only artist in her family. Her younger sister, the devoted Sarah, and their mother Catherine Augusta Mitchell (1812 to 1899) painted and drew the landscapes of their Tasmanian lives. Like so many other female artists, they are unknown because their artworks are regarded as domestic. Art was part of their “ornamental education” (young women of genteel families were taught to draw, play the piano and sing, embroider, sew and keep house) considered appropriate to women of their station.

The Mitchell women show us their lives in very different ways: Catherine Augusta and Sarah’s works are typical of the colonial society’s expectations – pencil drawings or picturesque water colour scenes to send home to England or to share with friends.

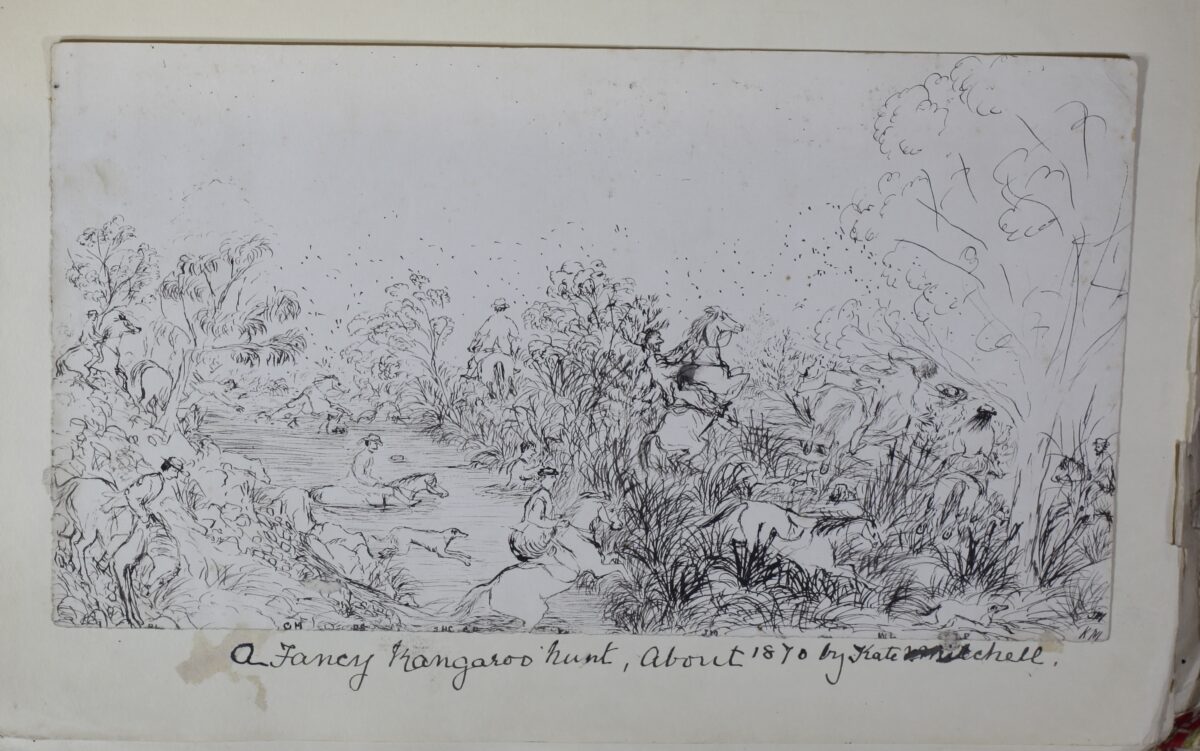

Kate’s work is unconventional not only for her gender but for the times. There is no historical evidence of colonial Australian artists using pen and ink to draw personal events and activities. The occasional pen and ink landscapes are found but these are often in private journals.¹

Her pictorial telling of their daily lives is bold, boisterous, funny, poignant, and informative and shatters any vision that these sisters and their female friends lived circumscribed lives – certainly not physically. Kate was determined to record detailed visual stories of the people who were part of her life; what the family achieved; how they and the community explored the land and the seas; what they overcame; and the dangers and consequences of their isolation.

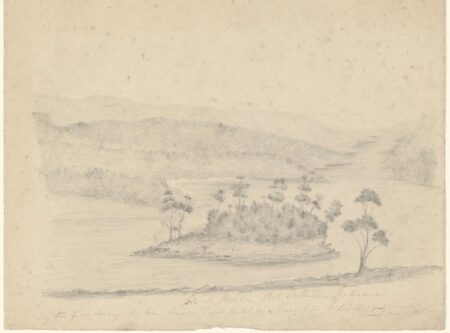

Later as Jane and I researched Kate and her sister Sarah, we made two unexpected and poignant discoveries. Catherine Augusta had drawn and painted her own memento mori of Port Arthur Isle of the Dead where, between 1841 and 1844, she buried two baby boys. She entitled the pencil drawing, Isle de Mort, Port Arthur, Tasmania, with the annotation, “my two first darlings lie here – Francis Keast Mitchell and Henry John Mitchell. First 8 months, second 10 months old”. This work is one of a number at the Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts, Hobart.

Catherine Augusta Mitchell’s pencil drawing of the Isle of the Dead where her two baby boys are buried. Image courtesy of the Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts Collection.

Catherine Augusta arrived from Cornwall in 1839 to marry fiancé John Mitchell and joined him at Port Arthur where he served a number of roles including superintendent for Point Puer boys’ prison until its closure in 1848.

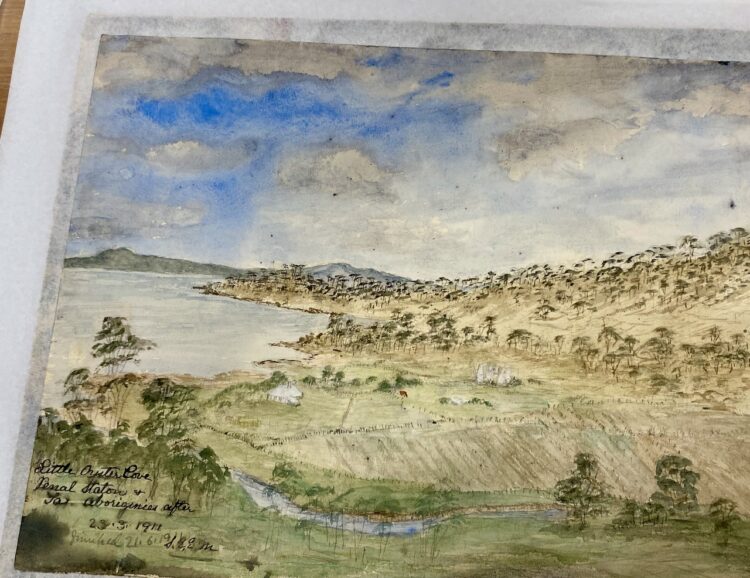

The second revelation came from the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG), when Jane was told of a wooden chest containing more than 770 watercolours painted by Sarah in the years after Kate’s death until sometime in 1937 when they were donated to the Museum. Many of Sarah’s works are glued to long strips of fine, black serge and it is thought this was a practical way to show the works to friends and family: she simply unfolded the fabric bundle.

One of more than 770 water colour images painted by Sarah Mitchell.

Sarah’s note: “Little Oyster Cove Penal Station and Tas. Aborigines after. 23/3/1911; finished 21/6/1911”

Image courtesy of Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery Collection.

Jane Giblin’s quest to excavate the lives of those who have been forgotten and disregarded is not new. In the past she focused on family and kin. For a major travelling exhibition, I Shed My Skin, A Furneaux Island Story 2019 to 2020, she created 91 works including black and white photographs, ink and pigment works on paper, and lithography from interviews with ancestors about their lives on Vansittart Island and the other islands in the Furneaux group. And there is a familial connection to the Mitchell women. Kate drew Jane’s female ancestor in many of her images.

The delicate and crumbling scrapbook cannot be displayed, so Jane commissioned artists Penny Carey Wells and Diane Perndt to reimagine it for our times: The Mitchell Women: unknown stories. Into its pages she has glued copies of Kate’s 200-plus works, along with Sarah’s words of explanation. The new scrapbook also includes copies of Jane’s paintings and lithographs in response to Kate’s drawings.

The scrapbook was first displayed in September and October 2023 at the Allport Museum and Fine Art Gallery and then travelled along with copies of some of Kate’s drawings to the Glamorgan Spring Bay Historical Society, Swansea. In late September 2024, it opened at the Arts and Cultural Centre in Bright, Victoria and in late November 2024 at theLaunceston Library. At each exhibition, Jane invites the public to create their own pen and ink drawings, paintings and writings for inclusion in the scrapbook.

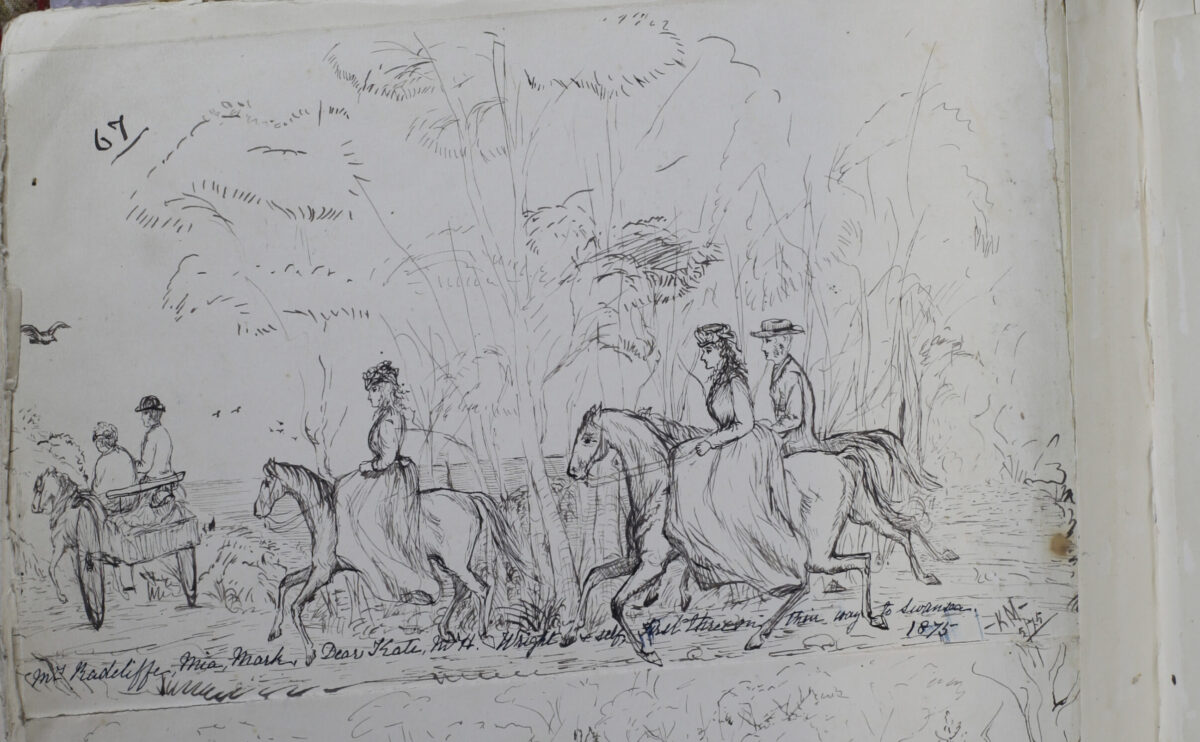

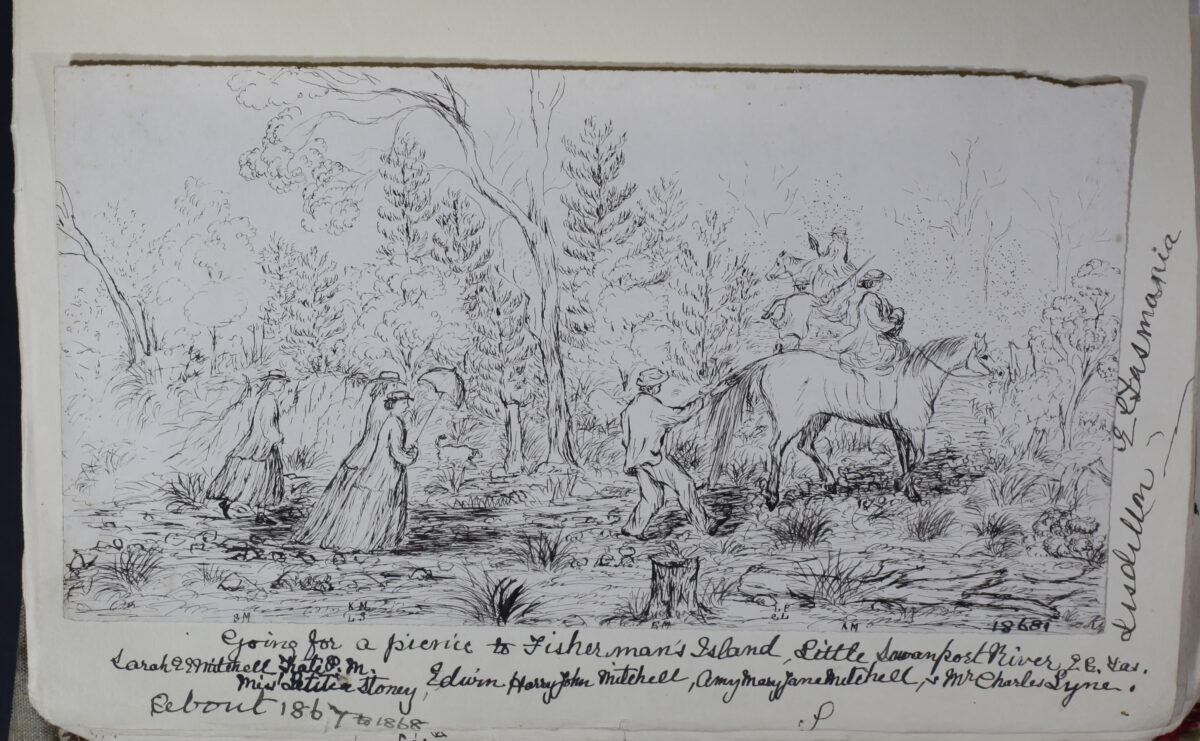

What captures our contemporary imaginations are Kate’s images of energetic women, of a certain style of dress and station, unfettered by any assumptions about how they should behave. They wore long full skirts, layered petticoats and buttoned-up blouses, and always a bonnet.

Strikingly to us, their behaviour appears in stark and impractical contrast to how they are dressed: they ride through wild, unexplored, densely forested hills and valleys, or through heavy, rolling waves, and bafflingly they do so side-saddle (or no saddle) wearing their long skirts, high-buttoned blouses, and bonnets. They ride galloping horses over fences and through the bush as they hunt wallabies or search for lost sheep.

And Sarah notes in her reminisces that Kate “was a wonderful rider and used to jump fences with ease and break in horses”. And the real-life consequences are also graphically recorded: Kate draws the women tumbling from their horses or from the carts they are driving. Sarah writes of scraped faces and broken arms and fingers but rarely serious injury. Kate draws their 4 am departures from Lisdillon on horseback for a three-day journey to Hobart. The sense of their spirit and energy is palpable.

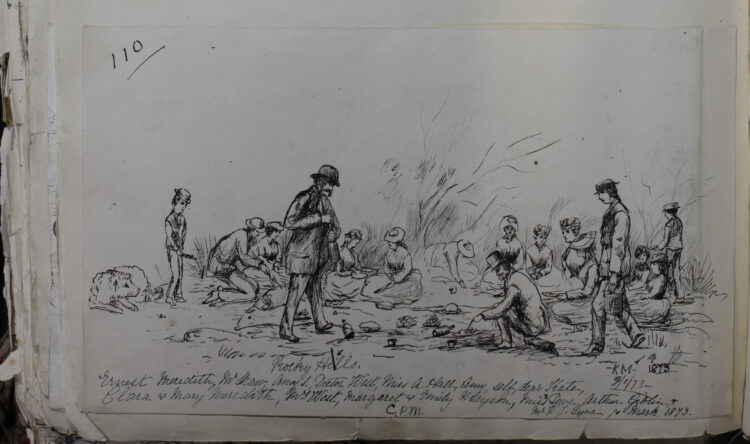

Sarah’s note: “Doctor West draws a cork”. Kate’s close drawing enabled Sarah to identify each of the guests, and note their names, years later. Drawing dated 1873.

Kate puts herself into most scenes: cooking chops over an open fire during a seaside picnic; poised with her fishing rod before launching herself off a log onto boggy soil; threatening to pour hot tea on two boys torturing a March fly; attending dances; wading thigh deep in her full skirt in the sea to bring a boat to shore; or heading out with her drawing book and her dog Caleb, carrying her easel strapped to his back.

This is Kate’s robust visual autobiography but she never identifies herself. However, her intent is clear: I am here, I am integral to this story and this community is mine, and she signs her drawings with a simple: “KM”. Today, we only know who she is in each story because Sarah has captioned her image: “Dear Kate” or “CPM”.

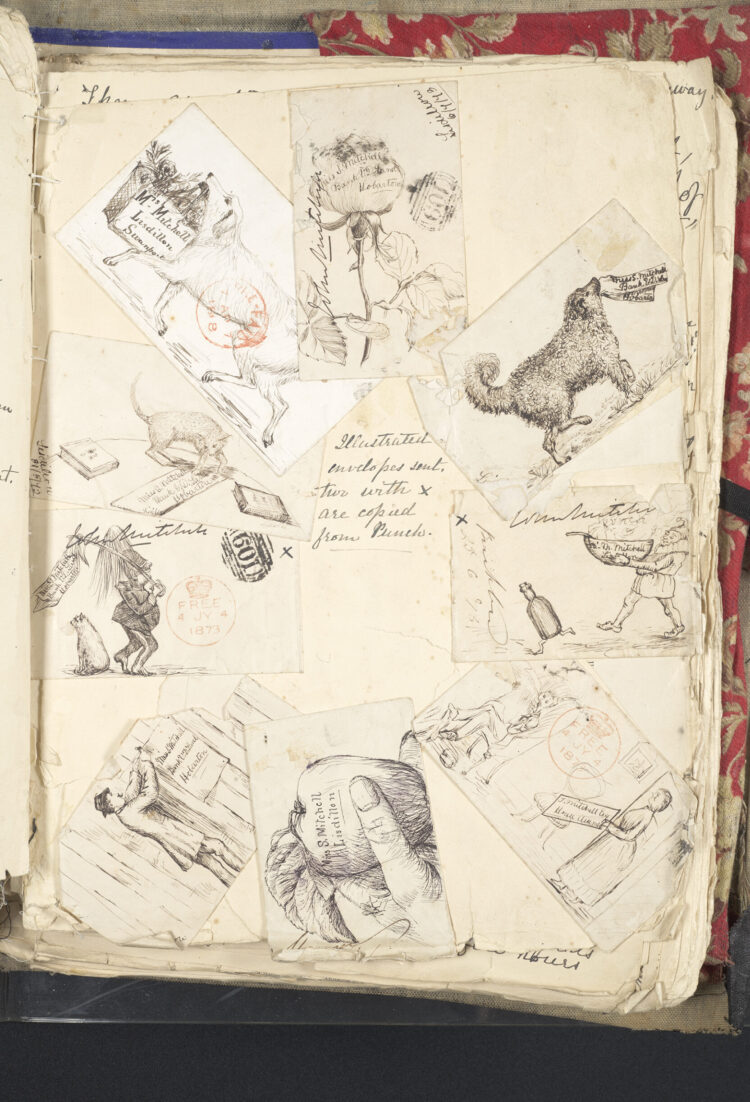

Kate’s drawings of people – her dominant subject – are not always deftly done, but over the years she became more skilled and accurate enough for Sarah and her niece Grace, years later, to identify many of the people in the scenes. The initial inspiration for her cartoon style and irrepressible commitment to action and realism is, Jane believes, Punch, the illustrated satirical magazine first published in London in 1841. Punch was a popular and appropriately middle-class publication, and for a brief time a Tasmanian Punch edition was published.

Kate’s illustrated envelopes addressed to friends; some copied from Punch magazine.

Did Kate and Sarah think about the traditional owners of their land and what these people had lost? In 1874, Sarah wrote that “Trugananni” [sic] had given their father a basket and a length of rope. And later in 1909 she donated the basket and rope to the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery (QVMAG), Launceston, stating: “It is a great treasure being Trugannini’s [sic] last basket she made.” Trucanini died in 1876, and there is no proof that this was her “last basket” but it does highlight some awareness by Sarah of the original people on whose lands they lived.

After studying Sarah’s paintings, Jane believes the two sisters sat and recalled the days’ events, the people and what they were doing and wearing. And Kate boldly allows her imagination the freedom to draw each scene.

Three women artists from one family painting and drawing with purpose: the first, Catherine Augusta following the approved practice of a Victorian gentlewoman drawing landscape scenes to send home to England with letters; her daughter Sarah, who we now know worked for many years after Kate’s death to produce not only Kate’s story but also an enormous collection of water colour landscapes, with the occasional solitary, distant figure to offer perspective; and most intriguingly Kate, whose intense gaze focuses in on her community, visiting dignitaries, and her family and how their lives intertwined.

Kate’s landscapes are not bucolic. She sees the landscape as the backdrop against which lives and events happen, although, occasionally, she records the unexpected native animal or flock of birds.

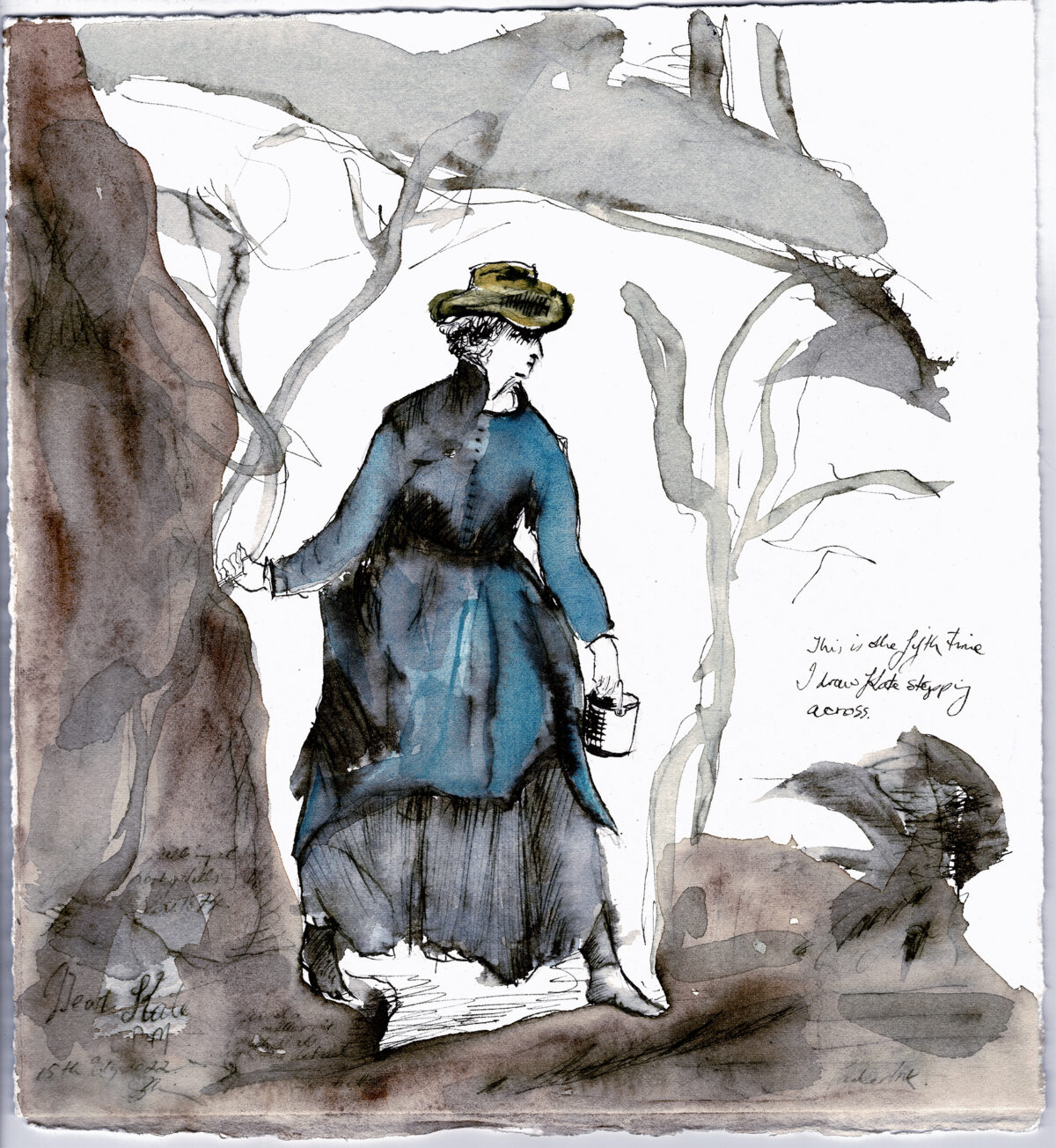

Jane Giblin (2022) Jane studied Kate’s drawings and detailed aspects showing her pen marks and detail. She has added her own colour imaginings.

And now we are here in our time with Jane Giblin. Jane has brought the Mitchell women back to us through her study of Kate’s work. And as she responds to Kate’s drawings with her own stroke and line, she begins to sense their mutual passion. Like Kate, Jane strides and rides (in her trusty 4WD) through the landscapes she loves from Tasmania’s east and northwest to the Furneaux Islands of her ancestry. Jane, like Kate, wants to understand not just who she is but how she has been shaped by this land and her community. Until encountering Kate, Jane did not include her own image in her works but now because of Kate, she feels compelled to do so. Jane describes her approach to Kate’s work,

“I started with her ink drawings, first, and I take an element that I respond to with very little thought. I looked for evidence of her particular skill…but then as time went on the story became more important than her mark. I was intrigued, for example, to capture the moment they were chasing sheep, there’s a possum she’s drawn in beyond her figure. And there’s her imaginative brilliance: drawing the women falling off the cart. Or the little moment when Kate is standing near a bog and there’s a little tiny dog standing beside her. She’s carrying the fishing gear, and [her figure] is only a centimetre tall, but everything you need is there. She’s tentatively standing on the edge of a swamp and being told to ‘Come on’. I am right there in the scene with her.

“We see action but it’s been reduced to the stylized rendering. I think that is a result of her doing it after the fact. Doing it, I strongly suspect, with Punch magazine in mind. She’s projecting herself into their storytelling mode. So, I believe she saw it and wanted to record her world.”

What can we surmise about Catherine Penwarne Mitchell? Was she the 19th century precursor to the 21th century “selfie-taker”? Yes, and she was much more. She ignored what society expected of her female abilities, and went boldly where few women had.

Poignantly, Kate’s last known drawing is of the Bright parsonage where she met her future husband the Reverend John Aubrey Ball. It’s a conventional and well executed pencil drawing of a house in a rural setting. We don’t actually know when it was drawn. Sarah has marked the date as “1876” – 18 months before Kate’s death.

Already something has changed: the artist is no longer Kate the bold story teller, she is Kate the conventional colonial woman. But had she lived beyond her 31 years, we wonder what else would she have shown us?

____________________

¹Lucy Gray (1840 – 1879) a colonial immigrant originally from Queensland, who spent a few months in Hobart for her health, also worked in pen and ink; however, her works were embedded as illustrations in journals and letters they were not a document of everyday life with images featuring one or two people. Meg Vivers, Castle to Colony, 2013, Brisbane: CopyRight Publishing Company Pty Ltd. And Caroline Jordan tells of Georgiana McCrae who had lessons on sketching landscapes in pen and ink with John Glover but she focused on miniature paintings: a much more acceptable path for a young woman. (Jordan, pp. 25 – 26)

***********

All historical imagery, except where noted, from The Sarah Mitchell Scrapbook by Catherine Penwarne Mitchell including annotations by Sarah and Grace Mitchell, courtesy of the Royal Society of Tasmania, also known as the Sarah Mitchell Diaries, RS 32/4.

Jane Giblin

(born Launceston, 1962; lives and works on Flinders Island, Tasmania) graduated from the Tasmanian School of Art, in 1984, After graduation, Jane spent an extra year enrolled in the printmaking department learning to etch and eventually she completed two Masters degrees, one in painting and one in lithography. In 2022, Jane enrolled in the University of Tasmania PhD program with the School of Creative Arts. She is represented by Penny Contemporary in Hobart, Fox Galleries in Melbourne, and Janet Clayton Gallery, online, in Sydney.

Left: Catherine Penwarne (Kate) Mitchell Right: Sarah Elizabeth Emma Mitchell