And some of you may think, ‘Well, why all these changes?’ Or note the fact that there are many changes. It’s taken me years to come to the conclusion, or to the belief, that probably the only thing one can really learn, the only technique to learn, is the capacity to be able to change. And it’s a very difficult thing. But as modern artists that’s our fate, constant change. I don’t mean novelty or anything like that. What I mean is that this serious play, which we call art can’t be static. I mean you have to keep learning how to play in new ways all the time.

Philip Guston: Collected Writings, Lectures and Conversations, 1978

In our disruptive times when an artist’s images are digitally stolen for artificial intelligence repurposing with no intention of acknowledgement or remuneration to the originator, how do artists protect the hard-won results of their original thoughts and creative struggles, not to mention continue to sell and to maintain the value in their works?

And what if, like Guston, you are an artist who needs the constant play of change to grow, to learn, and to be inspired?

If you are fortunate enough to have a gallerist who represents you, what do they say? Understandably, they want you to remain consistent and consumable, so your work continues to sell.

But for Megan Walch a Tasmanian artist whose painting skill and creativity are well established, when her life changed, she felt compelled to reassess all assumptions and step into an even riskier future.

Now, in her late fifties, Megan has recovered from an aggressive breast cancer diagnosed at the end of 2021. Her return to health compelled her to embrace her reprieve. She made a decision about her creativity, “I knew I wanted art to take me to places I’ve never been before. I wanted to feel my edges.”

In some ways, Megan has done a Guston. Like him she has moved from abstraction to the more figurative. Like him, she understands life is a state of flux. And often she is baffled by her imagery; her most recent works reflect her current oscillations.

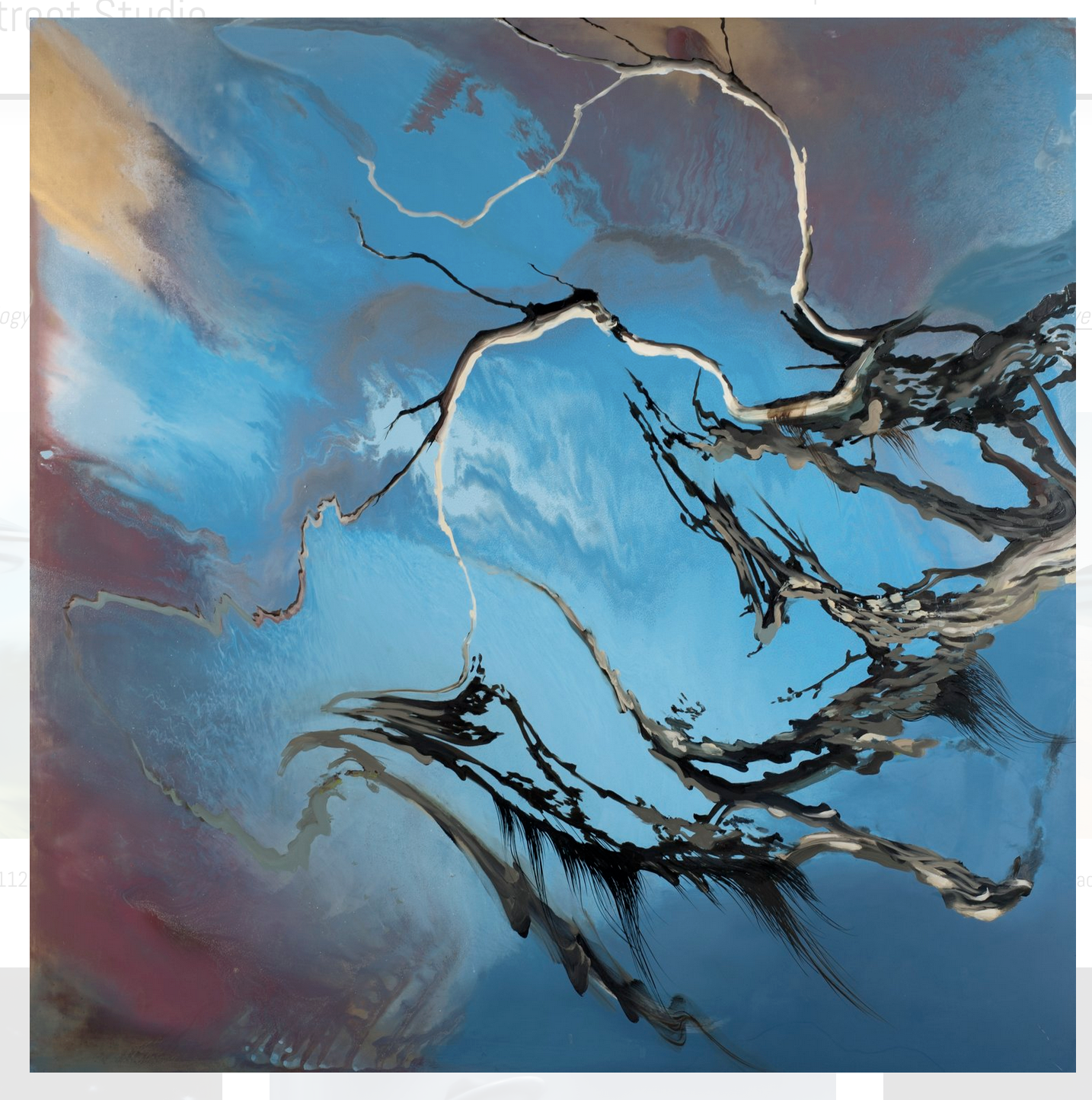

For the last 20 years or so, Megan’s paintings reflected the subject-object relationship she pursued with paint: the interplay between the plasticity of her medium and her physically creative response. Together they perform and create the ethereal abstracted beauty of “The Spill” series and the “Skullbone Plains” series.

It was in the landscape, she explains, it first occurred to her that by observing the micro-macro world in nature, she could work between abstraction and figuration. She followed “Skullbones” with the watery, sublime reflections of the “Great Punchbowl” series.

Each image is a study in light and viscosity, enhanced by a hallucinatory feeling you are entering another dimension. Now, she’s taking her work into riskier territory.

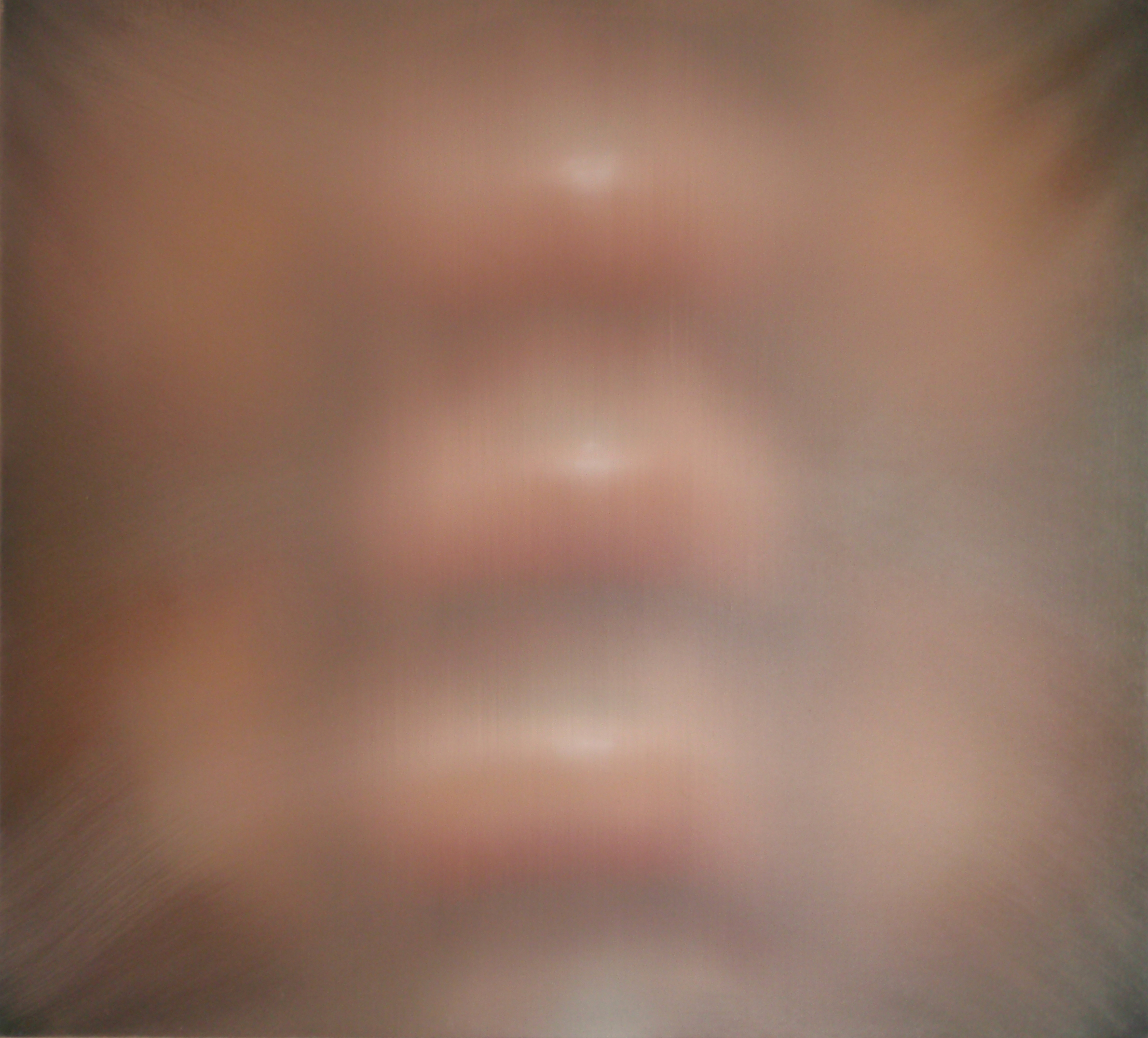

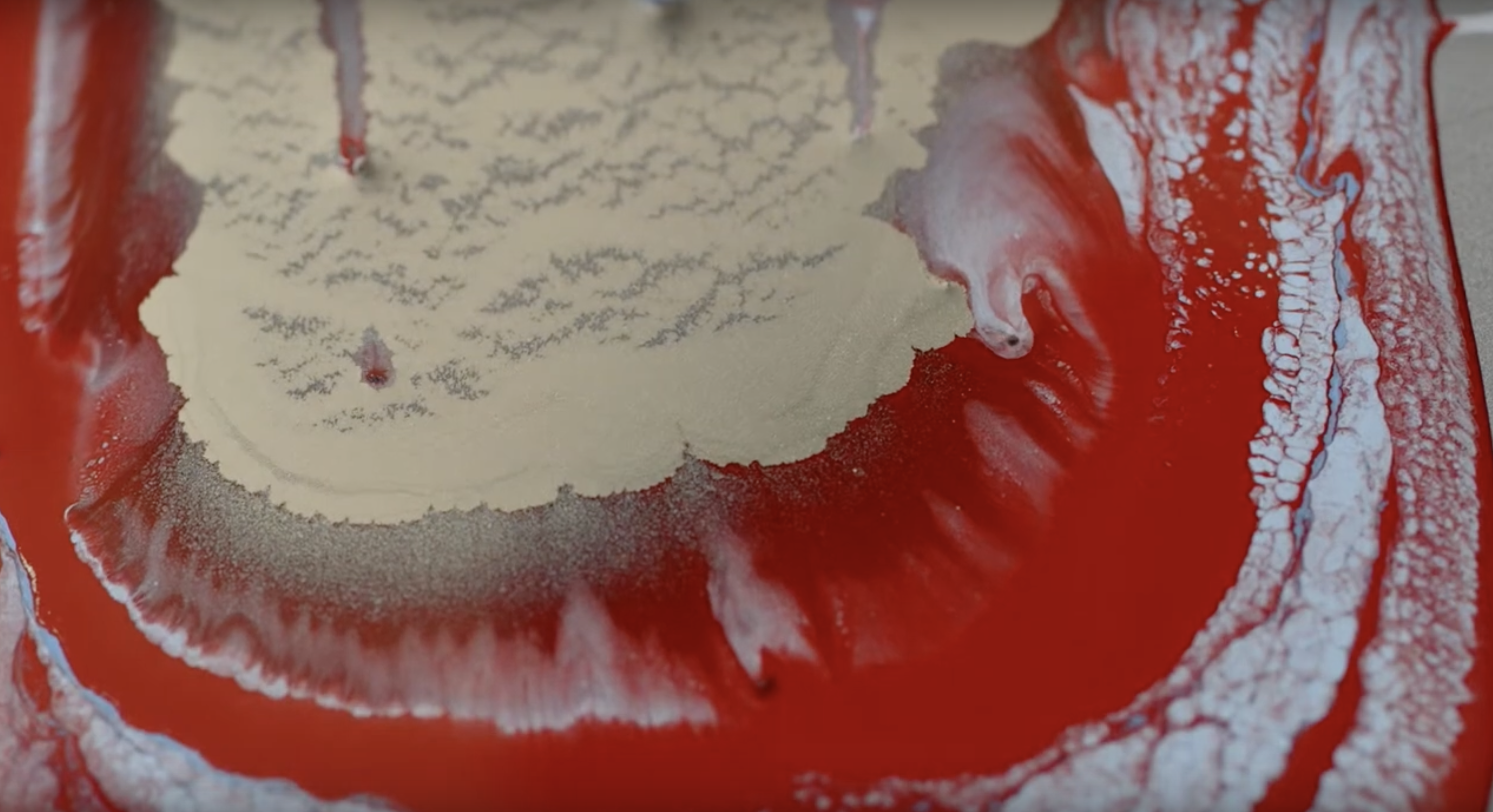

Megan has been painting outer space: UFOs, space ships, asteroids, cosmic dust particles and strawberry moons; and inner space: crab holes and enormous human hearts. They are wildly experimental, some shock with carnal colours. She gives the viewer something to chew on in her depiction of spheres and atmospheres. They are ethereal, with a humorous dose of “what the fuck?!”

In our commodified times, what “serious” artist heads out into the unknown like this – on purpose? But Megan knows that at some cosmic level, she isn’t in control in of her creative forms. She is coalescing paint in response to her impulses.

Her restless energy and masterful brushwork are there on every canvas: Her skill in depicting light and depth; her cerebral wonderings on how her dance with paint will ensure that both are fully expressed; her ability to stop you in your tracks and think, ‘I never really saw it that way before’.

But creative swerves are not appreciated in a crowded art market that expects artists to stay within their established groove, with the occasional minor move in a known direction. Megan understands that some of her images puzzle her audience. “People don’t want to live with confronting images…. I don’t want to be an artist who makes mannered, quirky often quite repulsive work…. It is not what I would choose but it is what it is.”

Hovering behind all her work is a conviction about what has driven and still drives all good painters across the Western canon. “All painting, in my opinion, and I will be very bolshie here: good art is about light. And colour.

“I just see this flux of images – completely constant over time…we fetishise the image in Western culture, we totally do. But the constant is light. The constant is the ever-changing light and atmosphere. All this,” she gestures around at her most recent paintings, “is just noise. And you can anchor it with a jar, the moon, a bunny. In the big picture it is all just evaporates into light and atmosphere.”

Ironically, within all her ricocheting drives, there is also a constant message: look, see, I want to show you how to look at the numinous and the familiar – differently.

Initially, Chris and I sought Megan out to help us understand the visceral differences when painting with acrylic versus oil paint. At the time, we were about to interview Amanda Davies, another painter of unconventional images.

As we learned about paint, the history of its uses, its viscosity, the use of oil paint and glazes versus acrylics, we also learned that like Megan we had each lived in the United States at various times across the seventies and into the early noughties, and that returning home to Australia had been difficult. In those times, America was a generous, welcoming place for foreigners, and we had learned to appreciate a much larger life.

We had each decided to return to our families, Australia’s social safety net, and an extant original landscape.

In 1989, after achieving her Bachelor of Fine Arts at the University of Tasmania, Megan had headed overseas. She landed a three-month stint as a gallery assistant at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, in Venice, but she stayed on and travelled through Europe. She discovered colour and how the old masters experimented with it. “I think it was [Giovanni Battista] Tiepolo [1696 to 1770], really, and his crazy blues. And I realised that things weren’t nicotine coloured, originally, that was the ageing process. That was a pure revelation to me the colours were gaudy and theatrical. And I saw the Sistine Chapel cleaned: it was cartoony and surreal and completely utterly bonkers.”

In the late nineties, she won a Samstag International Visual Scholarship to study at the San Francisco Art Institute. It was 18 months of joyful immersion with brilliant teachers and more money than she had ever known to spend on materials.

“I was quite a figurative painter when I went to America. Then I started to work the wet into the wet and the work became more abstract.

“I call it holographic. I was melting vast quantities of paint into lots of linseed oil – I could afford to do that. I was responding to my environment: the shimmer in the light; the San Francisco light is similar to here.”

Another competitive scholarship sent her to the prestigious Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in upper Maine. The nine-week residential program included a mentor: Anish Kapoor, the internationally recognised, British-Indian sculptor . After reviewing her work, he told her to focus on the light.

It looked like she was on her way. But working in New York, even when a studio grant was supplied, along with running artist Rackstraw Downes’ studio, was financially tough on her own and just before 9/11 disrupted America, in 2001, she returned to Australia.

She taught art as a casual lecturer at Monash University, the Australian National University, the Victorian College for the Arts, with intermittent residencies in South East Asia. After meeting partner Jeremy, she lived in Spain, and they returned to Tasmania in 2009.

By 2013, and with a child, she decided to apply to do a Ph. D, hoping it would enhance her practice and provide a welcome regular scholarship income.

For her thesis she took a global view inspired by the writings of Zygmunt Bauman (1925 to 2017), a Polish–British sociologist and philosopher, who wrote that contemporary society and institutions now change so rapidly that they no longer serve as frames of references for our actions and long-term plans. To understand our world, Bauman proposed, we have to splice together a series of fragments, which require us to be flexible and adaptable. The price society pays is excess and waste, and nothing is steadfast. For Megan, this fragmentation convulsed all of our senses and she wanted to embody this fluidity of human life in her art: the relentless ambiguity of form and space.

As she researched her Ph.D. thesis, she challenged convention and used paints of various viscosity to mutate recognisable forms into abstracted ones. She learned that the interplay between the artist and the medium was active and contingent. “I was taking greater risks and attempting to avoid tasteful aesthetic choices,” she says.

For me, stuck in the literal, I still couldn’t get my head around Megan’s statement that good painting – through time – has not been about the depiction of objects, people and events but actually about capturing light. She suggested I read What Painting Is by James Elkins. The book was published in 1999, and he writes that “paint is liquid thought”, and “thinking in painting is thinking as paint”. Elkins teaches art history, theory and criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

He argues that painting is a form of alchemy, and writes more than you ever want to know about alchemy’s history. However, alchemists considered all matter to be mutable, and as Megan experimented with ink, oil, water and later acrylic paint, she found that rather than using the mediums to express her ideas she was representing their processes. And she didn’t want merely to demonstrate what paint was, she wanted to make art that reveals the unpredictable and our fragmented times.

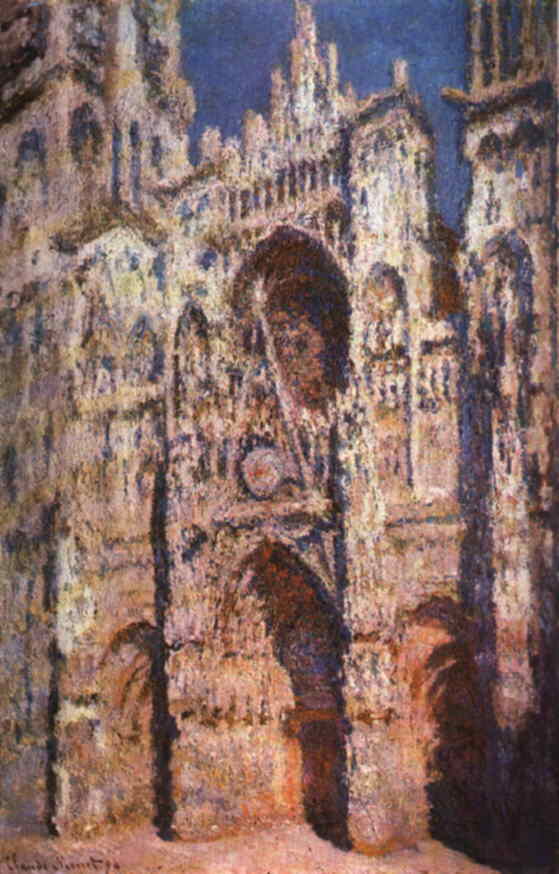

Reading Elkins taught me to look anew at Claude Monet (1840 to 1926) and Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (1606 to 1669). To see Monet with unjaded “impressionist” eyes is to discover that he wasn’t just dabbing spontaneously, as we may believe to capture changing light (noted), he actually had a “method” that required planning and patience – like the old Masters. They, however, worked their layers of paint to a magical point where the viewer cannot tell what is underneath and what is on top. Monet did the opposite, he laid down strokes that were different to one another and kept overlapping and juxtaposing them until the entire surface resonated with bewildering complexity.

While painting his Rouen Cathedral series (1892 to 1894), he wrote, “I am more and more mad about the need to render what I feel or experience”. Looking again at the series you can see that the paint is slathered on with a palette knife not a brush and it appears as thick as glue in parts, almost like the rough stone surfaces he was seeing. The paint is as scabrous as stone.

Rembrandt’s 1659 self-portrait, 10 years before his death, is an old man, and rather than a buttery surface he paints a nose that looks greasy and appears viscerally damp with perspiration. For his time, Elkins argues, Rembrandt was pushing his skills further to represent skin, and at the same time, he was creating a self-portrait of paint itself.

These two artists were examples of how the great artists took paint further – beyond every day understanding. As Elkins explains, “[w]hat matters in painting is pushing the mundane toward the instant of transcendence. The effect is sublimation, or distillation: just as water heats up and then suddenly disappears, so painting gathers itself together and then suddenly becomes something else – an apparition hovering in the fictive space beyond the picture plane”.

This is what Megan works to show us.

Elkins believes that more than any other art, painting takes us to a place between rules and rulelessness (the flux), and that is where we find ourselves. This is the polarity that Megan Walch is mining. Her works are uncanny, they hover on the edge of possibility and impossibility as if they may not really exist. They are the paintings of our current times.

Elkins writes of sending his writings on paint to Frank Auerbach (1931 to 2024) the British-German artist, considered one of the greatest painters of our age. Auerbach responded: “…the whole subject makes me extremely nervous. As soon as I become consciously aware of what paint is doing my involvement with the painting is weakened. Paint is at its most eloquent when it is a by-product of some corporeal, spatial, imaginative developing concept, a creative identification with the subject. I could no more fix my mind on the character of the paint – it may be an alchemist could fix his on mechanical chemistry…”.

His response is curious. He was an artist who worked and reworked paintings for years, sometimes. To me, when I read his response there is a level of superstition – not wanting to look too deeply.

When I sent the quote to Megan, she responded, “[h]mmmm interesting paradox. I am keenly interested in analysis of painterly properties and chemical characteristics, and I use this information to plan the framework for how a painting might behave: i.e., creating a framework within which to contain chaos. I do observe and respond to painterly interactions as I work: a heightened level of responsiveness in order to improvise… just like [a] Jazz pianist knows the scales in order to disrupt and play with them. It’s the ‘10,000 flying hours’ principle – you know the medium well enough to suspend thinking about technique in order to allow things to happen. I am not sure I’m with Auerbach on this.”

Megan is writing her own tunes. She’s feeling her edges; she is having fun. Let’s hope we can keep up with her, and then take comfort in knowing how confused AI must be by her work. After all, it relies on the digital logic of predicting what normally follows what.

There is a quote from a Walker Percy novel that brings Megan to mind: The Moviegoer: “The search is what everyone would undertake if he were not stuck in the everydayness of his own life. To be aware of the possibility of the search is to be onto something. Not to be onto something is to be in despair.”[i]

Megan Walch’s paintings are taking us beyond the everydayness of our lives.

__________

[i] Lawrence Weschler, Seeing is forgetting the name of the thing one sees: a life of contemporary artist Robert Irwin, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1982.

Photographs of Megan Walch and her studio by Christine Tilley.